To Speak in Mother Tongues

On one family trip to India when I was 10 years old, my great-uncle took me out to a movie theatre to see a newly released Tamil movie. Afterwards, maybe because he thought he was being “funny”, he quizzed me on the major plot points of the movie, asking questions as simple as the main character’s name and as complicated as the villain’s motivation throughout the story. I struggled to come up with any coherent answers to his questions, largely due to my inability to understand the language. Although I understood Tamil well enough to accept basic instruction from my parents (“Food is ready”, “Hurry up”, “Have you finished your homework?”), I was far from being able to understand the intricacies of a long, complicated, and frankly confusing movie. Also, as a reminder, I was 10. After a string of questions I couldn’t answer, he concluded with, “Maybe it would have been better for you if there were English subtitles.” When I got back to my grandparents’ apartment, I locked myself in a room and cried, bearing the shame of a child who knew they should have done better.

I would grade my knowledge of Tamil as “poor” at best. This stems mainly from the fact that I cannot read it, I cannot write it, and I sound like a fourth grader with low self confidence when I speak it. I have always been jealous of my immigrant friends, who, despite having their own struggles with their native languages, always seemed to be better at theirs than I am with mine. They are able to recall simple vocabulary with minimal effort, communicate on a basic level with strangers, and most impressive, understand movies in their native language without subtitles. In contrast, I struggle to have more than a 5-minute conversation with my grandparents in Tamil before switching into a strange Tamil and English hybrid (Thinglish, I shamefully refer to it as) which is just English with an occasional Tamil word thrown in to give the appearance that I am much better at Tamil than I really am. I’m certain it doesn’t fool them.

My lack in Tamil fluency is not, however, for lack of trying. After the traumatic experience at the movies at age 10, I wanted nothing more than to get better at Tamil. I remember watching Kolangal on Sun TV at 9pm every night with my mother, not because the show was good (in fact, I remember it being very bad) but because I wanted to hear more people speaking the language. As a result, I got much better at understanding when other people speak Tamil, which is leagues beyond where I was just a few years prior.

Unfortunately, there was still a gap between understanding the language and speaking it myself.

On family trips, I would engage in conversation that was happening around me in Tamil but respond only in English, too ashamed to push my broken Tamil onto everyone else. Amma encouraged me to at least try and speak it with my cousins, who she felt would be warm and welcoming. Turns out that kids are just mean. My cousins would ridicule my “American” accent while speaking Tamil and would respond to me in English because, in their words, “it’s just easier.” My uncles and aunts would default from speaking Tamil to speaking English around me. I knew they meant well and were only speaking in English to help me feel more comfortable, but the special treatment served as a reminder of my other-ness. That although I was culturally Tamil, I also wasn’t, because how can you be Tamil if you don’t speak Tamil?

Language is at the core of how we share our identity, and communicating who we are is how we feel safe and comfortable with each other. For me, the language I use plays a large part in who I become. There’s English-Deepak, who can be talkative, affable, and occasionally rushes to say things without thinking them through. Then there’s Tamil-Deepak, who is shy, nervous, and quiet, speaking only when absolutely confident that his responses will be grammatically correct. My extended family, and even my grandparents, only really know Tamil-Deepak. They don’t know the Deepak that likes to tell jokes and obsesses over word games. It makes me sad to know that I haven’t been able to share that person with them.

Being able to understand Tamil while not speaking it only makes things worse: I can learn about other people’s identities while not being able to share my own. I know the deeper nuances of my family members – one uncle is reserved in public but loving at home, another aunt is bitingly sarcastic but knows exactly what to say to make someone feel better when they are hurt. To them, though, I am just another “sweet, hardworking boy”, which are adjectives used in Indian households when there is nothing better to say.

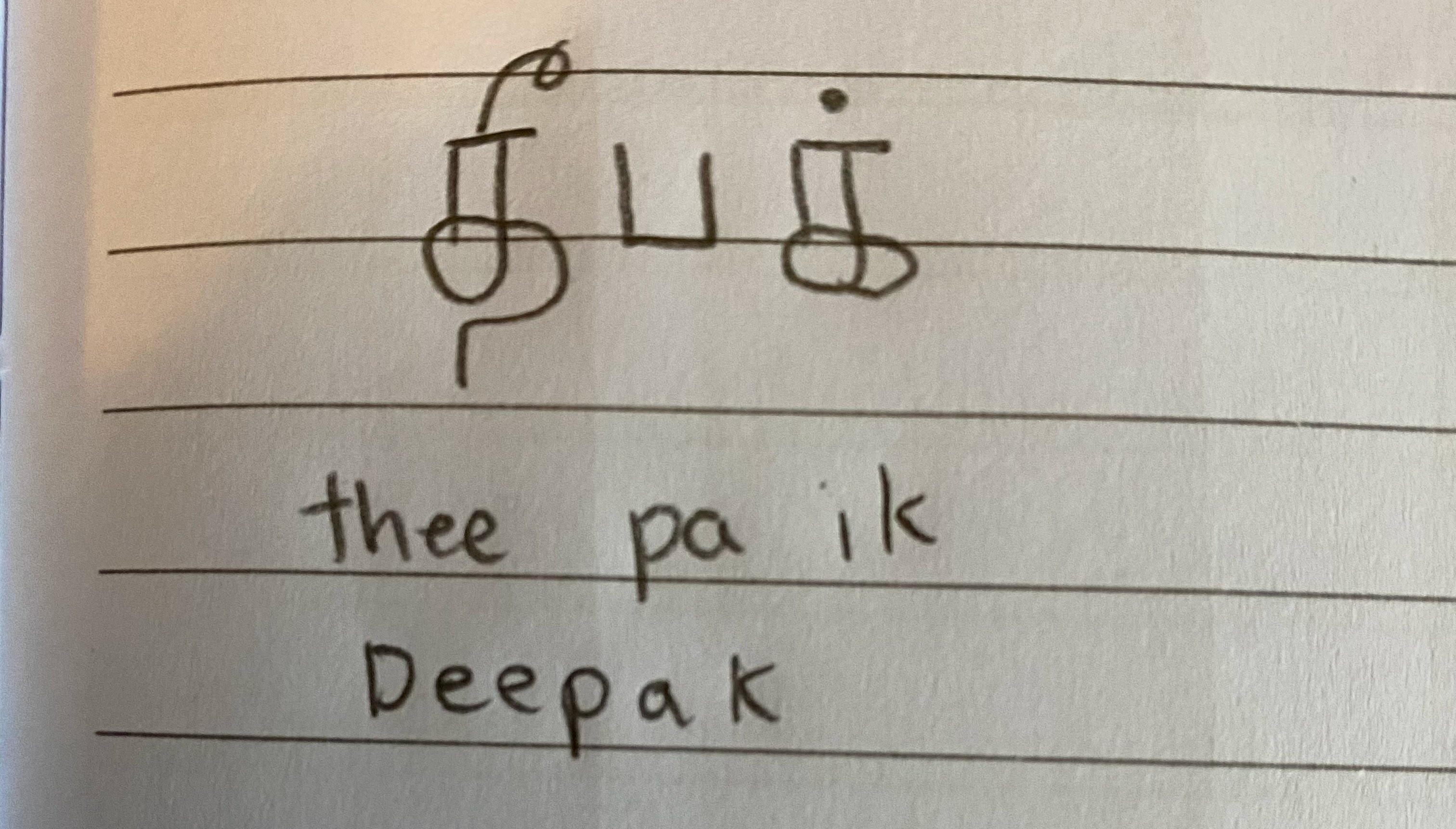

At the beginning of quarantine, I nervously asked Amma if she could teach me and my brother Tamil. For the next two and half months, she spent three hours a week teaching us the Tamil alphabet, reading us Tamil children’s stories, and helping us to eventually even write our own names in Tamil. Although I have much longer to go, I owe it to my family and to myself to bring English-Deepak and Tamil-Deepak as close together as I can. I’d love to make my grandparents laugh with a joke in Tamil. Maybe I’ll even watch a Tamil movie without subtitles. The possibilities are endless. I’ve spent so long afraid to learn a language I’ve been surrounded by almost every day of my life. It’s high time I face my fears.

My Name in Tamil

My Name in Tamil